Culture Heroes

Minor Moments

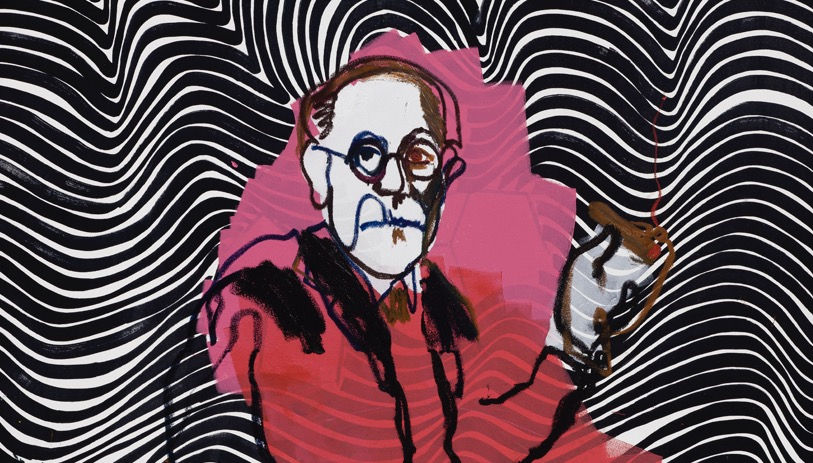

Eran Shakine’s Archive of Unofficial Histories

Since 2005, Eran Shakine has been constructing a personal archive of unofficial histories. Armed with an oil stick, a vivid imagination, and a mordant sense of humor, Shakine’s drawings weave their way through the annals of modernism and the heartbeat of contemporary culture in search of ‘minor moments.’ His idiosyncratic repository of famous and infamous cultural figures—artists, architects, fashion designers, musicians, and art-world glitterati—are rendered with an intimacy and irreverence that is habitually overshadowed by more heroic public narratives. Instead of accepting the scripted version of events, produced by well-orchestrated publicity photographs and legendary oral accounts, Shakine is interested in the lesser-known dimensions of his subjects. Though it may not be immediately apparent, this intimate gaze operates in two directions: It not only recasts the idealized icon as an individual with eccentricities and imperfections, but also asks the viewer to consider the extent to which Shakine is reflecting upon his own artistic practice and persona.

The series devoted to artists is perhaps the most transparent meditation on this theme. Much like a family gathering, there is a sense that Shakine is delving into a shared gene pool and exploring the affinities and contretemps that pervade familiar relations. A witty rejoinder to popular clichés about the majesty of the artistic process, these images expose the rarely seen fragility, isolation, and unceremonious conservation that goes hand in hand with aesthetic production. For instance, the existential bravado of Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, largely formed by Hans Namuth’s portraits from 1951, is summarily dispelled. In place of an inexhaustible choreography, we witness Pollock stretching his tired, aching back. Likewise, the aura of conceptual genius with which Marcel Duchamp has been anointed is transformed into sheer happenstance as he ‘discovers’ the readymade during a visit to the men’s bathroom; Josef Alber’s Homage to the Square materializes not so much from Bauhaus techniques, principles, and aspirations, but more prosaically in the semblance of a bright, yolky egg cooked sunny side up; and Pablo Picasso’s Guernica would not have become an anti- Fascist cri de coeur without the artist having clean brushes at hand. The delib- erations continue: What are the chan poster boy for Pop Art had he been born in the Middle East? Do we have faith in Joseph Beuys’ claims for mystical communion with a dead hare or, for that matter, with his public? And how would post-war art in Britain have turned out if Gilbert Proesch and George Passmore had not met at the Saint Martin’s School of Art in 1967? In these comical speculations, Shakine earnestly ponders whether art is an outcome of ‘genius,’ as some myths would have us believe, or whether it emerges from fortuitous events, uncertain situations, and an incredible amount of strenuous labor that only becomes minted as ‘virtuosic’ in retrospect.

In the series devoted to architects and fashion designers, Shakine suggests that the mystique of genius can only be sustained if we believe that a work of art leads an autonomous existence independently of its maker. To disembody the most eminent buildings and renowned couture of the twentieth century is to miss out on the more compelling and often zany aspects of creativity. Literally turning this lost opportunity on its head, Shakine coifs alpha-architects like Frank Lloyd Wright, Norman Foster, and Zaha Hadid with headpieces that resemble their own structural achievements. Similarly, he outfits fashion designers such as Yves Saint Laurent, Tom Ford, and John Galliano in their signature pieces. Shakine’s reattachment of modernist and contemporary masterworks to their inventor’s body, whether as millinery appendages or sartorial statements, prompts us to wonder whether academic histories can fully account for the tactile, sensual, desiring flows and fantasies from which cultural enterprises arise. Yet it would be going too far to suggest that Shakine links the meaning of aesthetic objects to the explicit intentionality of their authors or to the complicit interven- tion of the body. The quirky, compromising positions of his figures are probably not ones they would devise for themselves. But what if we caught them unaware? Indeed, the spectator is invited to join Shakine as an artful partner in crime and inquisitive voyeur; one fascinated by the libidinal undercurrents coursing unde- tected and unpatrolled through the channels of artistic expression.Though he may be piqued by the romance of aesthetic production, Shakine is equally attentive to the social codes of consumption. What is it that propels the public’s insatiable hunger for visual and cultural stimulation? How do museums, galleries, and mega art exhibitions frame the viewing experience? And how does the public distinguish itself from other players in the game—museum directors, collectors, and artists? By treating the characters and conventions within the art world as a sequence of interconnected vignettes, Shakine probes the well-oiled system that prepares the public for the short-lived moment— approximately ten seconds—they eventually spend with an artwork.

One of the most decisive aspects is the infrastructure of the space, whether it is the pristine architecture of the white cube, the information provided by the pithy wall labels, or the precise placement of benches in front of specific works. Perhaps less perceptible, there is a marketing machine that generates excitement for art consumption by boosting its symbolic value. Both newness and rarity are prime commodities with the gallery owner touting his or her latest addition to the stable and a museum displaying Vincent Van Gogh’s painting with respectful solemnity. An additional layer of rarified exclusivity is generated by the ‘buzz’ at the auctions and the branding of the must-see event of the year. You can almost hear the art jet set intoning, “Will I see you at Venice? Basel? Miami?” Operating together, these elements weave a subtle web of expectations around an art object, making it virtually impossible ever to have an unmediated, virgin encounter.

Shakine’s drawings are so poignant because they contain a dose of moxie but are completely free of cynicism. This is especially true in the ‘John and Yoko’ series, a tender tribute to rock’n’ roll’s royal couple that depicts the paramours as just two regular kids in love. Other than the silhouette of John’s guitar, there are no overt clues to their star status. In bed, on a walk, at a picnic, or in the bathtub, what strikes us most is the sweetness and simplicity of their companion- ship. The artist imagines what it would have been like for John and Yoko to have lived and loved apart from the hyper-exposure in the press that invaded their intimate life. In a protective gesture, Shakine uses his art to keep the men- acing world at bay and turns “The Ballad of John and Yoko” into a private tune. Interestingly, as the titles make clear, all the drawings in the series pre-date the couple’s wedding in March 1969—a distinct turning point in their own antics and tactics of self-representation. What followed, in bed-ins and demonstrations of ‘bagism,’ was an attempt to use their power as public figures to promote their campaign for peace. In this choice of dates, Shakine accentuates John and Yoko’s affinity in the year before their decision to court the camera’s glare and suggests, once again, that the public dimensions of an artist’s life are intimately connected to the private sphere. Could anthems like “Give Peace a Chance” and “Imagine” have been written if John had never met Yoko?

Shakine’s drawing technique plays a vital part in raising all these questions. With great fluidity and a quickness of execution, his images seem to emerge instantly, in the here and now, without any forethought or critical distance.

Yet, as he describes it, the drawings appear at the spur of the moment because of a sustained conceptual process. A wide spectrum of artist books, photographic documentation, and catalogues become arbitrary data bases for unstructured ‘research.’ Not every figure is a contender for immortalization; Shakine needs to identify with him or her before they become part of his lexicon. As each series gestates, specific episodes become tangible in his mind, and only then does he commit them impulsively to paper or canvas. It is not surprising, of course, that a meditation on artistic practice and its myriad myths should occupy an artist.

It is also not unexpected that he should delve into that unchartered, fertile zone between conceptualization and realization, or in Lou Reed’s famous lyrics, the lifetime that lies “between thought and expression.” In that sense, the motley crew of characters that populate Shakine’s highly personal archive represent various aspects of his own artistic persona in its complex intertwinement with his daily life at home and in the studio.

Working in Tel Aviv, a modernist city in the heart of the Middle East, might at times seem like a peripheral or solitary endeavor profoundly disconnected from the drumbeat of New York City, London, or Paris. Yet Shakine’s reshuffling of all narratives, including the one that dictates the relationship between ‘center’ and ‘periphery,’ reminds us that Tel Aviv is not at all a marginal location but is the ne plus ultra of modernist cities. It is here that he spends as much time rais- ing a close-knit family as being in the studio—a choice that may appear outside the norms of a milieu that reveres myths of creativity allied with mercurial in- tensity and narcissistic self-absorption at the expense of a deeply rooted family life. Yet these are only a few of the contradictions that have nurtured Shakine’s thirty-year career, one that encompasses a rich output of painting, sculpture, and installation, and embraces figuration and abstraction in equal measure.

If these multiple contexts help us shed light on Shakine’s drawings, there is something about their ‘attitude’ that also needs clarification. Though his droll transgressions bring the improbable to the fore, it would be wrong to characterize his works as either caricatures or cartoons. Instead, they resonate more closely with a graffiti artist’s covert operations, which test the line of cultural consensus that distinguishes between official cultures and subcultures. Nimble with his oil stick, he proceeds in the manner of a graffiti artist who, under the cover of night, ‘bombs’ sanctioned public spaces to voice marginal or alternative points of view lying dormant in their midst. Living in an uneasy co-habitation and vying for representation, dominant and minor narratives appear as two sides of the same coin. It takes an artist like Eran Shakine, with a palpable passion for modernist and contemporary art, to cross these tenuous frontiers and tip the balance of power momentarily towards the minor.

Caricature Development, ARTNews